Implementing UI

This is an attempt to document the process of implementing a web UI based on visual assets, functional requirements, and content specifications. Hopefully the steps below provide a framework for accomplishing work with a high fidelity to the original designs, but they are not a substitute for attention to detail and thorough understanding of HTML and CSS.

Contents

Start with the markup

When implementing a new UI or doing a design pass on existing code, it's usually a good idea to refer to the HTML output before looking at any CSS. HTML syntax may be simple, but it is also meaningful and can make the difference between a web app that is accessible and secure and one that is not. The HTML also defines the structure of the content and design elements on a page, and while CSS can be used to manipulate the visual output to a high degree, it can only go so far.

You can use browser dev tools to inspect elements and view the executed markup for a page. The markup should be structured, organized, and readable, even by someone who is not familiar with HTML. Elements that are related to each other should often be contained within a parent element, and semantic HTML should be used wherever possible. Take into consideration the organization of the content in the component or the page, and verify that the appropriate tags are being used. For example, if some content is a list, use a <ul>, <ol>, or <dl>, and if some content is tabular data, use <table>. <div> and <span> are both generic elements that can be used to divide content into groups or apply decorative styling, but on their own they have no inherent meaning, so usually they should be viewed as extraneous. It is fine to use <div> and <span>, but there should be a clear reason when doing so.

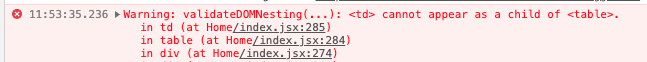

Some HTML elements have quirks around how the browser renders them (such as <legend>) or strict rules around what child elements are allowed and how they must be structured (such as <table>). It's important to familiarize yourself with elements like these in order to use them effectively. Fortunately, React will usually print out a console error when it detects invalid HTML, and it's important to notice and correct these errors since they can be an indicator of potential browser compatibility issues.

Ultimately, structuring the markup in a way that corresponds to the content of the page will make implementing a design easier, because it will define patterns and objects that also exist in the language of the design. For instance, if the design indicates a certain margin in between groups of text content, it might make sense to group that content using a <section>, <div> or other element, even if there's no other visual indication of separation such as a border or background color. Identifying the repeating components and subcomponents of a design will help establish the foundation upon which you can start styling with CSS.

Resources

Style with CSS (modules)

Before writing any CSS, it's important to understand the CSS that already exists within the application, and determine how your changes will build on top of that. By default, CSS is globally scoped, meaning any CSS that is imported anywhere has the potential to apply to markup in your application everywhere. For example, if you have the following component...

// component.css

.myComponent {

background-color: yellow;

}

p {

font-size: 16px;

color: blue;

}

// MyComponent.jsx

import styles from './component.css'

const MyComponent = () => <div className="myComponent"><p>This is a component!</p></div>

... it doesn’t matter whether or not that component is currently visible in the application -- that p style will apply to every <p> tag in your app on every page.

That isn't to say you should never write global CSS -- it is extremely useful when defining the default styles for the app, and the more CSS that can be shared and applied globally, the smaller your bundle size might be. However, if you are trying to write styles for a specific component or page, it is usually safest to use CSS modules.

// component.module.css

.myComponent {

background-color: yellow;

}

p {

font-size: 16px;

color: blue;

}

// MyComponent.jsx

import styles from './component.module.css'

const MyComponent = () => <div className={styles.myComponent}><p>This is a component!</p></div>

The above code snippet looks very similar, but with one key difference: the file name ends in .module.css. That tells the F/E compiler to hash any class names contained in that file. That means in the effective code, myComponent will end up looking something like component_myComponent_1a2b3c. Additionally, the .module.css file exports the hashed values as a JS object, so they can be referenced in JSX component code (see how styles.myComponent is used in the above snippet):

{

myComponent: 'component_myComponent_1a2b3c'

}

The compiled CSS & HTML will end up looking like this:

// CSS

.component_myComponent_1a2b3c {

background-color: yellow;

}

// HTML

<div class="component_myComponent_1a2b3c"><p>This is a component!</p></div>

However, you might notice the p style block in that file will still apply globally, since it is not nested under any CSS class. So the CSS module file should finally be updated to:

// component.module.css

.myComponent {

background-color: yellow;

}

.myComponent p {

font-size: 16px;

color: blue;

}

All of the above also applies to SASS/SCSS files (.scss, .module.scss).

References

CSS: less is more

Another reason to start with defining the HTML is because you will immediately get to see how far that gets you without writing any CSS at all. Most of the time, base styles such as typography and layout should be inherited by global CSS or top-level components. If additional styling on a page or component is needed, it's usually a good idea to verify with the designer whether it is a change that should occur globally or not, and if not then that's usually a signal that a new UI component is needed.

When adding a new UI component, it's easiest to first build it in a component library tool such as Storybook, outside of the context of the application. That will ensure there is no tight coupling to API data or other contexts, and the UI can be viewed and tested in isolation. Build the component with stories for each test case in mind, and expose props that might be needed when using the component in the application (such as for passing in API data and event handlers). Add a CSS module file for the component, make sure to scope all styles under a class, and add style declarations only as needed.

When it comes to adding CSS declarations, here are some guidelines:

-

Use existing variables/mixins for colors, spacing units, etc.

-

Avoid setting global margins on components. Setting margins on elements inside of components is fine, but use the sibling selectors (

+and~) where appropriate.-

For example, you can control the margin between specific elements. In this snippet, the space between an

h2andpwill be 15px, but the space between anh2and aulwill be 20px:h2 + p { margin-top: 15px; }

h2 + ul { margin-top: 20px; }

-

Ultimately, it's important to understand what each line of CSS is doing. Adding lines until something looks right is usually a recipe for unknown consequences, and can have effects on accessibility or add unnecessary kb to the bundle.

Finally, if you are using USWDS, it does expose some utility classes that can be used directly in the markup (such as margin-x-auto). Be cautious of using these unless something is truly an exception. The reason is that it adds additional points of dependencies between the styling and the markup (components will only have the expected visual result if they also have the correct classes) and adds more variables to where applied CSS may come from. For example, if a component is pulling CSS in from global styles, and a CSS modules file, and inline utility class names, it adds to the complexity of what styles will be effectively applied, and makes it harder to change or debug in the future.

References

Cheatsheet

-

Review the effective HTML in component code and dev tools

- Look for structure that aligns with the content, and no invalid DOM errors

- Avoid adding extraneous elements (such as

<div>s that have no purpose)

-

Ensure all type elements have the correct sizing and type styles

- Applies to

<p>, <h1>, <h2>, etc. as well as text inputs and any other elements with text content - Why? This will affect the resulting spacing, and inform any tweaks to padding & margin that may be needed

- Always define both

font-sizeandline-height(unitless, as a factor offont-size)

- Applies to

-

Know the differences between padding and margin

- Padding is used to add internal spacing between an element’s content and its border

- Padding does not collapse - it will always effectively be what you declare in the CSS

- Margin is used to add external spacing between two elements

- Margins collapse: if two sibling elements declare margins that overlap, the larger margin will be the effective space between them

- For example, there will be a 35px margin between these two

divs:

.divA { margin: 20px; }

.divB { margin: 35px; }

<div class="divA"></div>

<div class="divB"></div>- TODO: Add a diagram that illustrates collapsing margins

-

Compare the implementation side-by-side with the design at mobile size (< 600px wide)

- Spacing inside of elements (padding inside of a box, margins between child elements)

- Vertical spacing between elements

- Background colors and borders of elements

- Any touch targets (inputs, buttons, etc.) should have a minimum size of 42x42px (this does not apply to inline text links)

-

Resize the window up to tablet and desktop sizes (> 800px wide) and compare the implementation side-by-side with the design

- Spacing inside of elements (padding inside of a box, margins between child elements)

- Vertical spacing between elements

- Any layout changes as a result of the window size increasing

- Background colors and borders of elements

- Responsive type scales up as indicated

-

Double-check implementations in different browsers and devices as needed

References

- Can I Use? - use to check browser support for new CSS/JS features